What are screens before the screen

As previously stated, the screen is a continuous development. This section tries to take a media archaeological approach to point out early practices that hinted at some elements of constructing a screen, including the illusion, the mechanism, the environment, and the materiality of a plane.

In particular, the perspective formalised in the fifteenth century has intervened in the process of creating an in-depth scene on a two-dimensional plane along with a frame, and the technique developed further around the sixteenth century when Albrecht Dürer described a kind of perspective machine that can be seen as a technical object. Furthermore, the camera obscura discovered in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in my view, is an automatic machine for making and verifying perspectives where images are produced unmediated and thus perceived as authentic and isolated.

The following content will discuss these objects or practices and how they relate to screens in more detail.

The Early Perspective

There are two historical moments for the perspective, and Anne Friedberg stated them as Alberti’s window and Brunelleschi’s mirror[16]. In 1435, Italian painter, architect, and scholar Leon Battista Alberti published the De Pictura (On Painting), which is regarded as the first text theorising how painters could use perspective to draw realistic paintings. Before the publication of this book, around 1420, the famous architect Filippo Brunelleschi experimented on how a perspectival painting can be illusive to the eyes when compared with physical architecture.

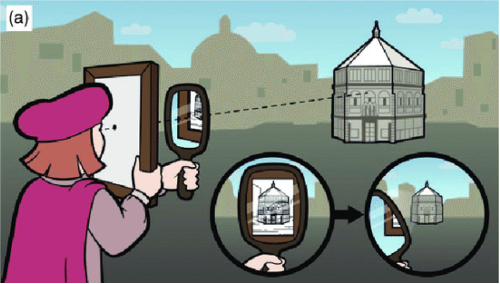

Let’s start with Brunelleschi’s experiment (fig. 1). The experiment has the following elements: the Florentine Baptistery, a panel depicting the perspectival image of the baptistery with a small hole on it, and a mirror. During the experiment, Brunelleschi stood in front of the baptistery where the vantage point corresponds with the vanishing point of the perspectival painting, so that the physical and the pictural baptistery are identical regarding their perspective. Then, Brunelleschi held the panel with its back towards him with one hand and viewed the perspectival image of the baptistery from the reflection of the mirror that was held with the other hand in front of the depicted side through the small hole on the panel[17]. As a result of this setting, when applying and removing the mirror in front of the panel, spectators “felt that he saw the actual scene when he looked at the painting”[18].

This straightforward empirical experiment proved how illusive a perspectival image can be using simple but interpretative methods and tools similar to how the screen does today. However, before entering the discussion, it would be better to summarise what the perspective is in Alberti’s theory so that this thesis can reference them all together.

In the 1435 book, Alberti described how a perspectival painting should be worked on, which begins with the famous quotation: “First of all, on the surface on which I am going to paint, I draw a rectangle of whatever size I want, which I regard as an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen”[19]. The rectangle here is particularly vital – it is not only a drawn frame inside of another frame (the frame of the canvas or panel) but, more importantly, a frame focusing on the natural ways of seeing and a resizable rectangle according to the needs of the artist that is metaphorised as a window and serves as a reference object to calculate the perspective geometrically. As Friedberg stated: “Alberti was a geometer of vision; he recast the visual coordinates of space into the geometrics of triangle, pyramid, and intersection”[20].

Taking a deeper look at Brunelleschi’s experiment and Alberti’s methodology of conceiving a painting, they both represented some preconditions to the formation of the screen this thesis wants to articulate while remaining prominently distinguishable from it. Fundamentally, the ways of seeing under the linear single perspective are sight-centred, rationalised, and represent a natural scene because of its illusiveness where the eye believed it was looking at the physical baptistery. As Friedberg refers to Erwin Panofsky, the perspective is “transformed ‘psychophysiological space’ into a ‘mathematical space’, ordered and rational”[21] with a “single and immobile eye”[22], which “the perspective may be understood with equal justice as a triumph of the distancing and objectifying sense of the real and as a triumph of the distance-denying human struggle for control”[23] and thus this kind of single-point perspective is strongly conflated with the Cartesian subject for which is “centred and stable, autonomous and thinking, standing outside of the world”[24].

The same epistemological situation goes the same with contemporary screens, but part of it. For screens, especially computer screens, it is often perceived as a loyal output machine that instantly displays every keystroke of keyboards and every coordinate of the movement of mouses – word processors print out every character on a digital sheet when writing an essay, terminal applications pop out every response from a remote server or port when debugging errors, and there are many other examples. In such circumstances, the screen serves as a monitor for its users: it visually renders the result of inputs in the form of pixels and RGB colours, where characters and words have a preciously relative location and colour calculated by algorithms and mapped accordingly on screens in which the application frames (as windows) are resizable based on the needs of users. Also, in such circumstances, users stay away from the screen physically, in which they are sitting on a chair, immobilised, with the computer screen placed on a desk in front of them, stretching their arms to reach the keyboard and mouse, staring at the screen, contemplating – as audiences standing still in front of classic artworks in art museums.

However, as previously written, both Alberti’s window and Brunelleschi’s mirror are distinguishable from today’s screen – while that kind of difference is also related to the perspective, I shall reveal them later in this thesis.

Before continuing to the next section, it would be necessary to go back to Alberti and his metaphor of windows. In the same 1435 book, Alberti described another frame called the velo (veil), which is “a grid-like netting stretched on a frame” and is supposed to be put “between the eye and the object to be presented.”[25] Therefore, the veil is a window of aid, letting through the light of the object, then allowing the painter to regenerate the perspective on their working paper, which they could copy and paste coordinates rather than calculate the perspective with lines and rectangles on the working plane. Leonardo Da Vincy already utilises such aid in Alberti’s time, but the later mechanism described by Albrecht Dürer is clearer and more well-documented for the discussion of this thesis.

Perspective Machines

Dürer’s aiding veil did not change significantly compared to Alberti’s – they were both using a frame in between the painter and the object to be painted, with a series of threads to measure the positions of the coordinates and transfer the coordinates to the plane to be painted. The perspective was all geometric in their methods, but Alberti’s was more calculative, while Dürer’s was more mechanic.

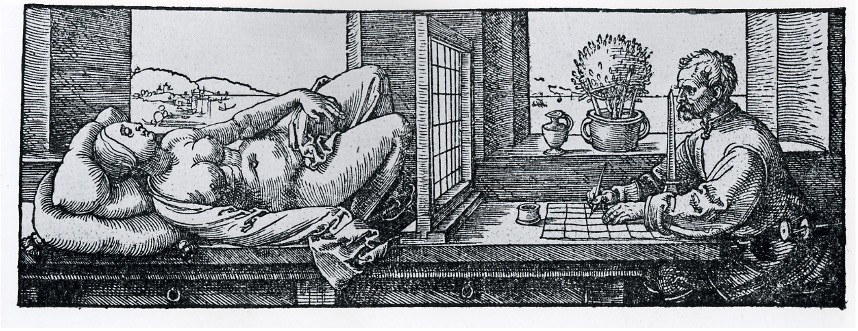

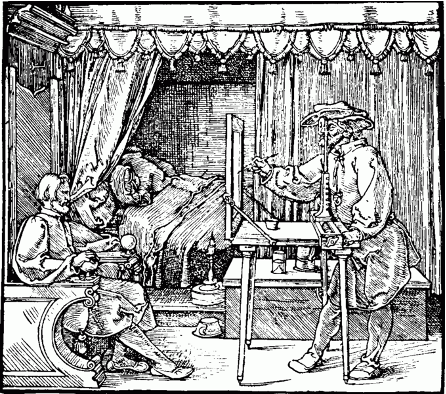

In the book Underweysung der Messung (The Painter’s Manual)[26], published in Nuremberg in 1538, Dürer created some of his best-known woodcuts depicting how he recommended painters at his age draw a perspectival image.

The first woodcut (fig. 2) shows the first method of using a frame with grids and a fixed viewfinder to sustain the viewing point. To get a precise perspective, painters using this method only need to transfer the coordinates that appear behind the grids to the gridded drawing plate in front of them. The second woodcut (fig. 3) illustrates a more complicated method that requires an assistant to stretch a string to the edges of the object the painter wants to paint as anchors while the painter places their pen at the spot where the string passes through the frame. When spots are confirmed, the assistant closes the shutter to leave perspectival markers on the drawing plane. The third woodcut (fig. 4) depicts a more advanced and direct method – a transparent object, like glass, is mounted in the frame, enabling the painter to directly draw the perspectival image on the frame as long as they find themselves the correct viewing point with the fixed viewing finder.

These are the perspectival machines, and they have much in common, which resonates with the screen this thesis wants to emphasise. Overall, they are objects in between the subject (the painter) and the object that allow painters to achieve a precise linear single perspective. As previously cited, the perspective represents an ordered and rational epistemology that viewers are put in a designed and immobilised position. For perspectival works in the Italian high Renaissance period that took Alberti’s methodology, drawing aiding lines or frames on their painting plane, such as Da Vincy’s Virgin of the Rocks (1483-86), Pietro Perugino’s The Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter (1482) and more, audiences tend to be in one fixed scientific position to enjoy the illusiveness of the painting[i]. However, with perspective machines, artists are further involved and positioned in a similar scientific circumstance – they rely on this kind of mechanic machine, and the machine has its rules of operating – artists’ eyes submitted to the viewfinder and frame to find the correct spot, artists’ hands regulated by the frame and the desk to limit the scale of scenes to be included, and the distance with the object prolonged to ensure the space to operate the machine. Here, artists are users of the perspective machine.

All in all, the perspective machine has become a technical object, which “is thought and constructed by man, is not limited to simply creating a mediation between man and nature; it is a stable mixture of the human and the natural, it contains human and natural aspects; it gives its human content a structure comparable to that of natural objects, and allow for the integration of this human reality into the world of natural causes and effects.”[27] That is much alike today’s screen, where users have to be equipped with it to see what is behind the screen – be it your partner on the other side of the world or the code that is knitted to fabricate a website, you name it – users of screens are artists seeking for perspective, getting a refined-natural perspective while being mediated by it.

So Close to a Screen

This section will discuss a more advanced technical object compared to Dürer’s perspective machine, which created an enclosed and separated environment: the camera obscura.

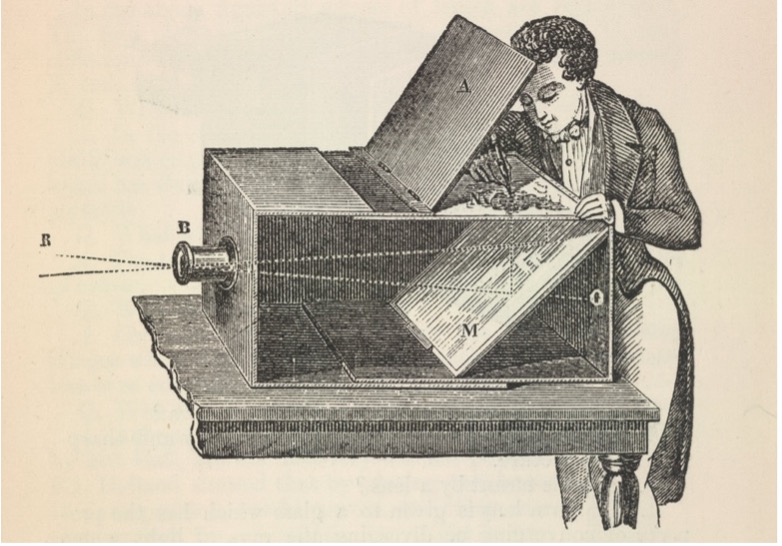

A camera obscura can be simple or complicated. In general, it needs a dark space with a small hole connecting to the outside, and when correctly set, images outside of the dark space will be projected inside of the space in an up-side-down condition (fig. 5). As Jonathon Crary pointed out, the camera obscura was a paradigm at that time to study the relationship between the subject (observer) and the object (world)[28], it could also be referenced as one of the anchoring points for this thesis.

The thesis previously discusses how Dürer instructed painters to construct perspectives with the help of his perspective machines. In a similar context, the Dutch old master Johannes Vermeer was also believed to have used camera obscura to assist his creations because scholars[29] have found traces of using camera obscura in his paintings. Though whether and how Vermeer has used camera obscura is still under debate among art historians, it would not be a major concern for me because this section is focused on the object itself and perception changes brought in by camera obscura that can be traced in Vermeer’s works.

Let’s take a look at the elements building a camera obscura and what someone can get from it: a dark space, a small hole on the edge of the space, a plane in the space to receive the projected image, a possible lens to enhance the quality of the image, and series possible mirrors to reflect the image at a desired angle; as a result, someone could automatically get a clear, perspectival, unmodified, seemingly unmediated image from the camera obscura. To the extent of this thesis, though the components are not drastically different from Dürer’s perspective machines which are the necessary materials to build a technical object, the result of camera obscura and its metaphoric meanings are particularly vital.

Two illustrations (fig. 6 and fig. 7) introduced two variations of the camera obscura in a science compendium book published in 1874[30] can help to answer why the result is essential. Both of them are used to generate identical images of the scene for their users. When compared to Dürer’s machine, they are capable of automatically projecting a more precise perspectival image without measuring the object back and forth, also allowing their users to be able to draw a picture on the same plane in accordance with the projected image. They are more advanced technical objects assembling multiple technical objects (the mirror, the lens) into one that conceals themselves during the process of mediating scenes outside and thus both versatile and portable – as Simondon indicated: “technical object can be grouped with other technical objects according to such or such setup [montage]: the technical world offers an indefinite availability of groupings and connects”[31]. Through this process, their products are presented as unmediated, unmodified, and optically authentic so that their users are convinced by them, integrated into them, and furthering the myth of objective and distancing-denying single perspective mentioned above.

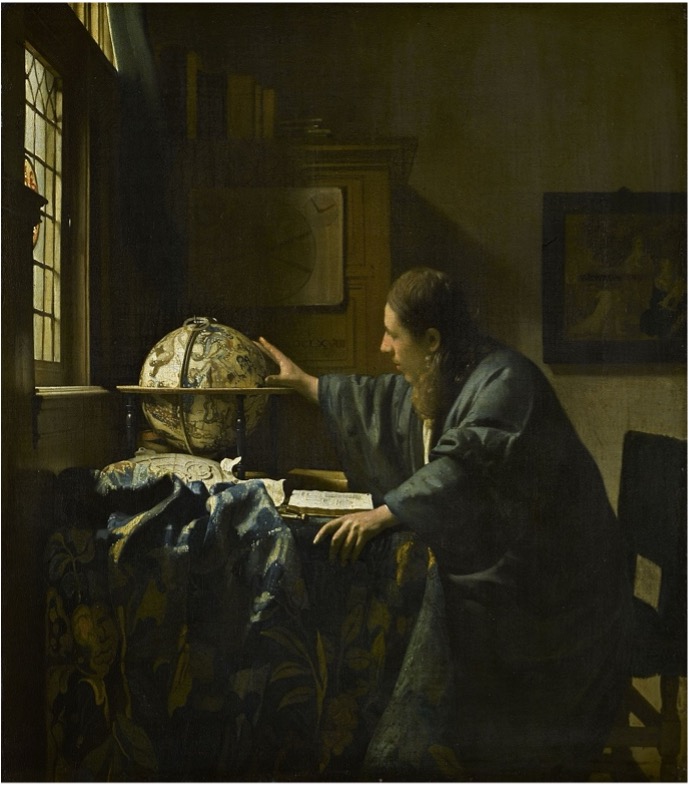

In terms of the environment and space, Crary, once again, did provide some valuable philosophical arguments. He not only confirmed what this thesis has stated by saying: “the camera obscura performs an operation of individuation, that is, it necessarily defines an isolated, enclosed, and autonomous within its dark confines”[32], but also pointed out the camera obscura as a device to “to sunder the act of seeing from the physical body of the observer, to decorporealize vision”[33] that makes the camera obscura as a machine directing to abstraction while remaining unmediated and enhancing a kind of objective. To give examples of his arguments, he analysed two of Vermeer’s works painted in 1668 (fig. 8 and fig. 9) on their symbolic and metaphoric interpretations related to Cartesian epistemology of mind[34]. He suggested rooms depicted in the paintings are the interface between the observer and the world, by which its interior elements, including the celestial globe and the map in front of the male person, are comparable to the imaging of camera obscura – projecting the outer world into a two-dimensional surface so that the male can think the world on these representations. In comparison, this sounds similar to how we use screens nowadays, for example, reading news or making physical changes through screens, but the milieu underneath them is radically different.